Presented as part of the requirement for an award within the Academic Regulations for Taught Provision at the University of Gloucestershire.

Acknowledgements

Deserving thanks and appreciation go to my Dissertation Supervisor, Bill Burford for his continual encouragement, support and feedback. Further thanks are also extended to David Booth, Vincent Marley and Jamie Liversidge for valued advice throughout the writing of this dissertation.

This dissertation would not have happened without the participation of my interviewees. Their expertise and valued content were a cornerstone of my writing to help answer my research question. Their enthusiasm and involvement are endlessly appreciated.

Finally, to my other half, my love, who has been by my side, protecting me from the storms and picking me up when I fall.

Table of Contents

2.0 List of Figures and Tables. 8

7.1 Topics outside the scope of this dissertation: 20

8.2 Theme 1- Main Barriers to SuDS Implementation. 22

8.2.1 Policy and Legislation. 22

8.3 Theme 2 – Sustainability. 27

8.3.1 1 in 30 and 1 in 100-Year Storm Events. 27

8.4 Theme 3 – Professional Skill Base and Perceptions. 28

8.4.1 Language and Terminology. 28

8.5 Theme 4 – Adopters and Maintenance. 30

8.5.1 Maintenance, adoption and management 30

8.6 Theme 5 – Data Collection and Analysis. 32

8.7 Literature Review Conclusion. 33

9.2 Research Theoretical Framework. 35

9.4 Sampling and Data Collection. 37

9.6 Data Analysis Techniques. 38

9.7 Mitigating ethical issues: 39

10.2 Theme 1: Main Barriers to SuDS Implementation. 42

10.3 Theme 2: Sustainability. 44

10.4 Theme 3: Professional Skill Base and Perceptions. 44

10.4.1 Knowledge/Perspectives. 44

10.5 Theme 4: Adopters and Maintenance. 45

10.6 Theme 5: Data Collection and Analysis. 46

11.2 Legislation, Manual and Guidance. 50

1.0 Abstract

The world’s climate is changing dramatically, with more erratic weather and increasingly intensive storms (Seneviratne et al., 2021). The current infrastructure in the UK does not seem to be holding up to the fast-changing weather patterns (Allard, 2021). This dissertation explores the barriers to integrated and innovative Sustainable Urban Drainage Systems (SuDS). Furthermore, how these flood mitigation systems can be effectively adapted to withstand and mitigate 1 in 100-year storm events whilst minimising adverse effects on neighbouring land, drainage systems, and waterways creating a homogenous, holistic living landscape.

The research will use qualitative research methods by means of ten semi-structured online interviews with industry professionals and a detailed literature review of relevant academic studies, guidance manuals, and policy documents with subsequent qualitative and quantitative research analysis. The interviews explored existing standards, expert opinions, behaviours, and strategies; the literature review examined a deeper understanding of industry perspectives, procedures, and behaviours.

Despite SuDS well-documented benefits (Environment Agency, 2021), their implementation remains hindered by inadequate legislation, failing maintenance protocols and misconceptions about their costs and practical applications (Burnett et al., 2024). The research concluded that developers often opt for simplified SuDS solutions, avoiding the most effective sustainable designs due to presumed cost savings, inadequate statutory legislation and poor industry awareness. Legislation remains a critical area for improvement, as inconsistencies and ambiguities in statutory and non-statutory documents perpetuate existing barriers.

Ultimately, a shift in SuDS perception to reclassify them as critical infrastructure similar to other utilities is vital to ensure that new developments are equipped with effective, integrated, sustainable flood mitigation systems that are resilient to future climatic challenges.

2.0 List of Figures and Tables

Table 1 – GI and SuDS Definitions. 29

Table 2 – Research Methods. 36

Table 4 – Participant Occupation Expertise. 40

Table 5 – Participant Barrier Contribution. 41

Table 6 – Barriers Considered Throughout the Discussion. 50

Table 7 – The Number of Experts Who Contributed to Each Theme. 85

Table 8 – Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria. 86

Table 9 – A List of SuDS Components and Benefits. 99

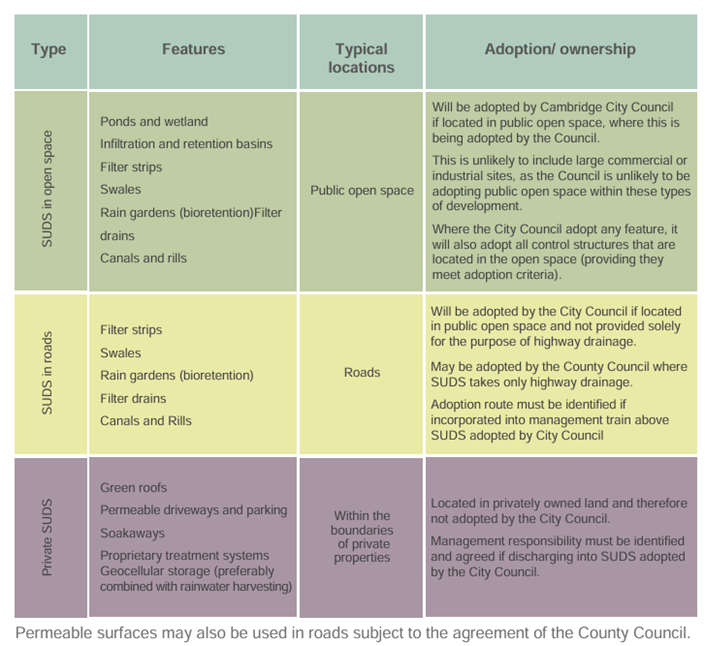

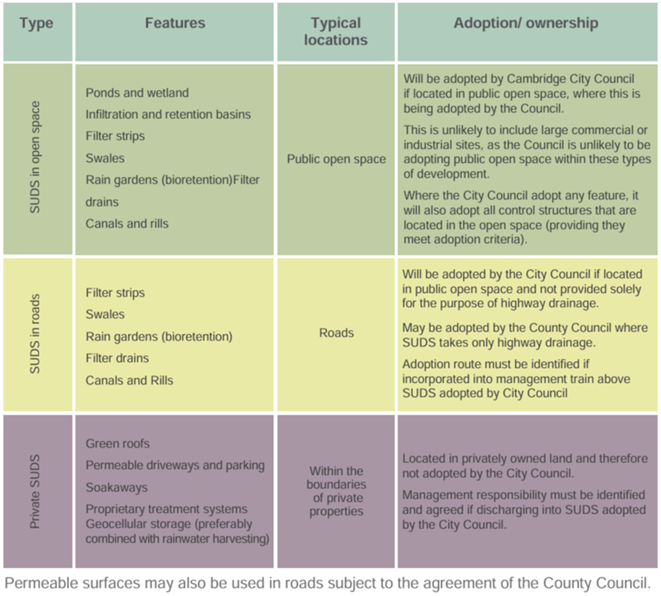

Table 10 – Cambridge Design and Adoption Guide Table. 103

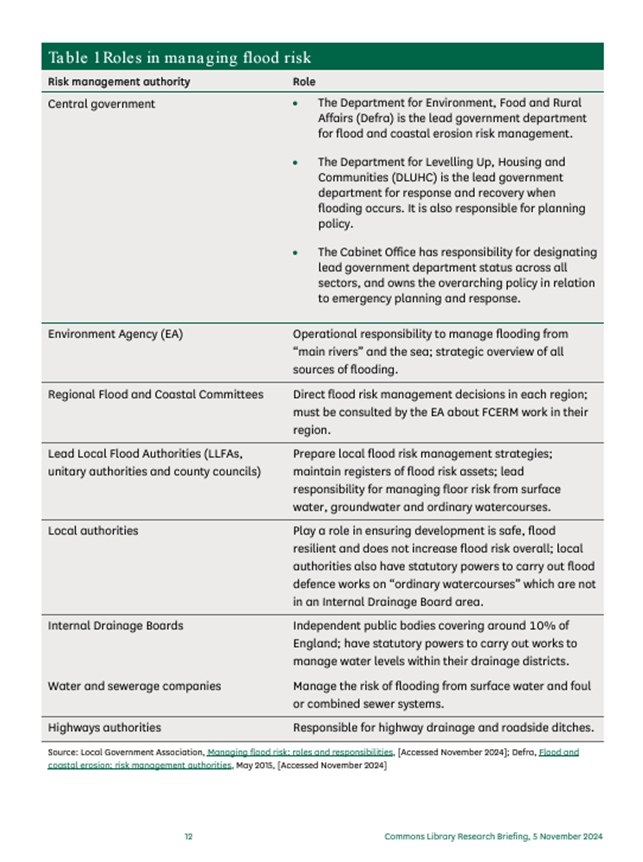

Table 11 – Flood Risk Management Funding Responsibility. 104

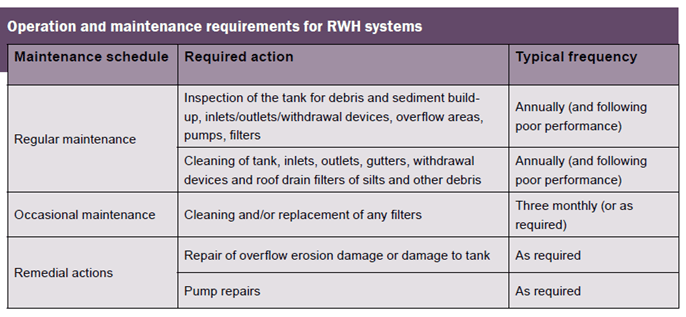

Table 12 – Example Table of Maintenance Recommendations. 105

Table 13 – Theme That Answered the Research Objectives. 106

Table 14 – Adoption Restriction. 107

3.0 List of Figures

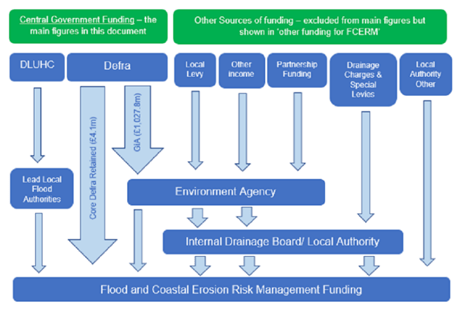

Figure 1 – The Funding Responsibility Flow Chart 24

Figure 3 – SuDS Maintenance Standards. 31

Figure 4 – Number of Experts Identifying a Specific Barrier. 41

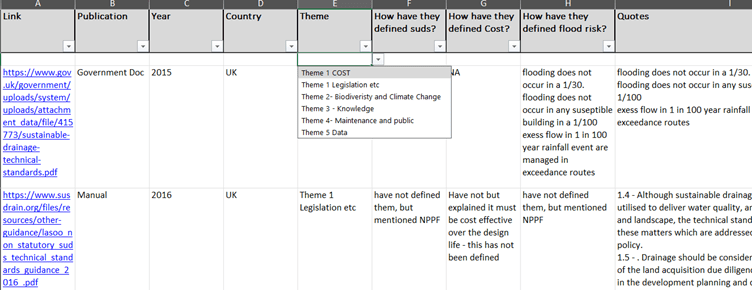

Figure 5 – Sample of Populated Excel Spreadsheet 84

Figure 6 – Sample of all fields within the Excel Literature Review Matrix. 84

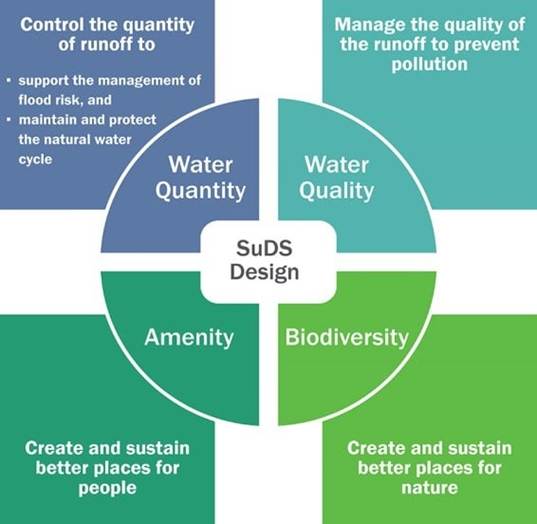

Figure 7 – Four Pillars of SuDS. 98

Figure 8 – Example of Boolean Research Method. 101

Figure 9 – Cambridge Design and Adoption Guide Flow Chart 102

4.0 Appendices Contents

Appendix A – Email of Request 76

Appendix B – One-to-One Interview Questions. 78

Appendix C – Follow-Up Email with Questions. 80

Appendix D – SuDS and GI Definition Matrix. 81

Appendix E- Literature Review Coding Matrix. 84

Appendix F – The Number of Experts Who Contributed to Each Theme. 85

Appendix G – Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria. 86

Appendix H – Coded Interview Finding Summary. 87

Appendix I – Four Pillars of Suds. 98

Appendix J – A List of SuDS Components and Benefits. 99

Appendix K – List of Professionals. 100

Appendix L – An Example Boolean Research. 101

Appendix M – Cambridge Design and Adoption Guide Flow Chart Table. 102

Appendix N – Flood Risk Management Funding Responsibility Table. 104

Appendix O – Example Table of Maintenance Recommendations. 105

Appendix P – Themes That Answered the Research Objective. 106

Appendix Q – Adoption Restriction Table. 107

5.0 List of Abbreviations

| 1/1. | 1 in 1-year Storms |

| 1/100 | 1 in 100-year Storms |

| 1/30. | 1 in 30-year Storms |

| BNG | Biodiversity Net Gain |

| CIRIA | Construction Industry Research and Information Association |

| DEFRA | Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs |

| EA | Environment Agency |

| FWMA | Flood Water Management Act 2010 |

| GBI | Green and Blue Infrastructure aka Green-Blue or Blue-Green Infrastructure |

| GI | Green Infrastructure |

| LA | Local Authority |

| LGA | Local Government Association |

| LPA | Local planning authorities |

| NHBC | National House Building Council |

| NPPF | National Planning Policy Framework |

| OFWAT | Water Services Regulation Authority |

| ONS | Office of National Statistics |

| Pn | Denote the participant anonymity code of an interviewee. |

| ROI | Return on Investment |

| S3 | Schedule 3 |

| SAB | SuDS Approving Body |

| SDEM | Sustainable Drainage Explanatory Memorandum |

| SuDS | Sustainable Drainage Systems |

| WSUD | Water Sensitive Urban Design |

6.0 Glossary

| 1 in 1 year rainfall/storm event | An event that has a probability of occurring, on average, once a year. The depth of rainfall for the event will depend on the duration of the event being considered (LASOO, 2016). |

| 1 in 100-year rainfall/storm event | An event that has a probability of occurring, on average, of 1% in any one year. The depth of rainfall for the event will depend on the duration of the event being considered (LASOO, 2016). |

| 1 in 30-year rainfall event | An event that has a probability of occurring, on average, of 3.3% in any one year. The depth of rainfall for the event will depend on the duration of the event being considered (LASOO, 2016). |

| Adopter(s) | Local Authorities or an organisation that will take responsibility for the SuDS after the developers’ period has ended (LASOO, 2016). |

| Amenity value | Characteristics that are deemed to be a benefit of a piece of property (Savills, 2024). |

| Attenuation Ponds | also referred to as rainwater attenuation basins, are engineered structures designed to manage and control excess rainwater and help prevent flooding. These ponds act as temporary reservoirs, strategically placed to collect and detain rainwater runoff, slowly releasing the water by infiltration or into waterways (Knight, 2024) |

| Blue space | Areas dominated by surface waterbodies or watercourses (White et al., 2020). |

| Capital Funding | Money that is spent on investment and resources that will create growth in the future. It typically involves building or major refurbishment of flood defence assets (Burnett et al., 2024). |

| Commuted Sums | A one-off payment of a capital sum made as a contribution towards the future maintenance of an asset to be adopted. Commuted sums generally relate to payments made by developers through bespoke legal agreements (White et al., 2020). |

| Component | Is a drainage feature that can take many different forms, e.g. Swale, Green Roof (LASOO, 2016) |

| Critical infrastructure | Systems, facilities and assets that are vital for the functioning of society and the economy (IBM, 2024). |

| Cumulative Sum | A cumulative sum is a sequence of partial sums of a given sequence, where each term is the sum of all preceding terms (Wolfram Research, Inc., no date). |

| Curtilage | The area of land around a building or group of buildings which is for the private use of the occupants of the buildings (LASOO, 2016). |

| Design life of the development | Dependent on the nature of the site and development. Typically, 60 years for commercial development (LASOO, 2016). |

| Discharge Compliance Limits | The limit to permit a water flow rate of a site (Environment Agency, 2019). |

| Drainage strategy | A document containing the full design, construction, operation and maintenance details of a drainage system to manage surface water. This document will form part of the drainage application which is submitted to the local planning authority for determination (LASOO, 2016). |

| Drainage system | All the components that convey the water to a point of discharge (LASOO, 2016). |

| End-of-line SUDS | SuDS components are generally used at the end of a SuDS management train such as basins and swales (McLeod and Mickovski., 2024). |

| Evapotranspiration | The sum of all processes by which water moves from the land surface to the atmosphere via evaporation and transpiration (USGS, 2019) . |

| Exceedance | An event that exceeds the capabilities of the surface water drainage system could be excessive rainfall, or blockage or a combination of tidal and pluvial events Non-Statutory Technical Standards for Sustainable Drainage: Practice Guidance 27 (White et al., 2020). |

| Exceedance flow | Is the overflow of water from a drainage system that occurs when the rainfall is greater than the capacity of the system (White et al., 2020). |

| Experts | An umbrella term used for the purpose of this dissertation only, including all participants taking part in the dissertation interviews. These professions included Developers, Landscape Architects, Drainage Engineers, Government Advisor, Project Managers, and SuDs Component Specialist. |

| Four pillars of SuDS | Refer to appendix H |

| Gentrification | Gentrification is the process of changing the character of a neighbourhood through the influx of more affluent residents and businesses (Finio, 2021). |

| Green Infrastructure | A strategically planned network of natural and semi-natural areas with other environmental features, designed and managed to deliver a wide range of ecosystem services, while also enhancing biodiversity (European Commission, 2024). |

| Green space | Greenspace refers to urban parks and wetlands, including public parks, street verges, cemeteries, and sports grounds that comprise some vegetation (Taylor and Hochuli, 2017). |

| Greenfield runoff rate | The rate/speed per hour/min of runoff that would occur from the site in its undeveloped and, therefore, undisturbed state (LASOO, 2016). |

| Greenfield runoff volume | The volume/amount of runoff that would occur from the site in its undeveloped and, therefore, undisturbed state (LASOO, 2016). |

| Hard Landscape | Non-living elements in landscape design/architecture, including paving, structures, and roads (Blake, 2015). |

| Impermeable area | All paved or roof areas that are not specifically designed to be permeable (LASOO, 2016). |

| Industry | To include that of Construction, Design and Planning. This list is not exhaustive. |

| Infiltration | Is where water is allowed to soak into the ground (LASOO, 2016). |

| Integrated system/management | Is to link drainage components within areas, including landscape, adoptive areas and curtilage, providing a basic framework for balancing competing demands within a given area (Reed, Deakin, and Sunderland, 2015). |

| Interception | Is preventing runoff from leaving a site for the majority of small rainfall events (LASOO, 2016). |

| Maintenance | Means the on-going maintenance of all elements of the sustainable drainage system (including mechanical components) and will include elements such as; on-going inspections relating to performance and asset condition assessments, operation costs, regular maintenance, remedial works and irregular maintenance (LASOO, 2016). |

| Non-potable water | It is stored water that is not suitable for human consumption; however, it has a wide variety of uses that are essential in our everyday lives, including plumbing, gardening, washing machine water, toilet and urinal flushing (Wooldridge, 2024). |

| Peak rate of runoff | Is the highest rate of flow from a defined catchment area assuming that rainfall is uniformly distributed over the drainage area, considering the entire drainage area as a single unit and estimation of flow at the most downstream destination(s) only (LASOO, 2016). |

| Pn | Denote the participant anonymity code of an interviewee. |

| Previously developed land | Also referred to as brownfield development that is no longer in use (LASOO, 2016) |

| Professionals | An umbrella term used for the purpose of this dissertation only, including professions working within this industry, including Developers, Landscape Architects, Drainage Engineers, and Planners. |

| Resource Funding | Money that is spent on day-to-day resources and administration costs. Amongst other things, it covers spending on routine maintenance of defences. It can( also be referred to as revenue spending (Burnett et al., 2024). |

| SAB | SuDS Approval Body has statutory responsibility for approving and, in some cases, adopting and maintaining the approved drainage systems (Monmouthshire County Council, 2022) . |

| Single property drainage system | This is the constituent parts of a drainage system within the curtilage of a single property and that only receive flows from that property (LASOO, 2016). |

| Soft Landscape | Living elements in landscape design/architecture, including green and blue infrastructure, grass, verges, and plants (Blake, 2015). |

| Sponge capacity | The ability and capacity of a component or soil to hold/store water (Luo, Pan and Liu, 2020). |

| Structural integrity | Ensures that a system fulfils its design function (LASOO, 2016). |

| SuDS/SUDS | Suburban drainage systems and sustainable drainage systems – used interchangeably. SuDS give equal consideration to controlling water quantity, improving water quality, providing opportunities for amenity and improving biodiversity. Similar to a natural catchment, a combination of drainage features (also known as components) work together in sequence to form a management train (Woods Ballard et al., 2015). |

| Susdrain | Community that provides a range of resources for those involved in delivering sustainable drainage systems (Susdrain, no date). |

| Sustainable drainage | Aims to imitate the natural drainage of a site before any development (Woods Ballard et al., 2015). |

| Swale | It is a SuDS component that is similar to a wide, shallow ditch but with a flat bottom (Woods Ballard et al., 2015). |

| The Management Train | Is a sequence of components that are connected together to drain surface water from a site. Controls both flows and volumes, as well as treating surface runoff to improve water quality. The fundamental principle is to slow down the movement of surface water runoff or encourage it to infiltrate into the ground to reduce its impact further down the catchment (Woods Ballard et al., 2015). |

| Urban Creep | This is the conversion of permeable surfaces to impermeable over time e.g. impermeable surfacing of front gardens to provide additional parking spaces, extensions to existing buildings, creation of large patio areas. The consideration of urban creep (is best) assessed on a site-by-site basis but is limited to residential development only. It is important that the appropriate allowance for urban creep is included in the design of the drainage system over the lifetime of the proposed development (Mcdonnell and Motta, 2021). |

7.0 Introduction

The construction of new developments in the UK requires the installation of sustainable drainage systems (SuDS) to reduce and mitigate the potential consequences of the increased surface water on the site (Woods Ballard et al., 2015). This research investigates the barriers affecting the efficacy of SuDS schemes and their creative innovation within green infrastructure (GI) which may be limiting their potential for effective water attenuation during storm events. With the engineering capabilities available, it should be feasible to design green and blue infrastructure (GBI) that safely manages water on-site during a 1-in-100-year storm event (1/100) without posing risks to buildings or infrastructure.

This dissertation explores the challenges to deeper integration of SuDS and green infrastructure (GI) in design and implementation. The research examines the viability of mitigating a 1/100 storm event using cohesive SuDS-GI strategies while safeguarding buildings, hardscapes, and infrastructure. The research also aims to identify ways to address these challenges in future residential developments.

The research will investigate how new developments prioritise the design and building of SuDS regarding aesthetic, environmental and commercial viability. Furthermore, the research highlights opportunities for developers to improve Biodiversity Net Gain (BNG) scores and for landscape architects and engineers to create bespoke, ecologically rich spaces, making developments more attractive for all stakeholders.

For the purpose of this dissertation:

- ‘SuDS’ refers to all the SuDS components either individually or as an integrated system, unless stated otherwise. A complete list of SuDS components, including their benefits, can be found in Table 9 within Appendix J.

- ‘Professionals’ will mean all skilled professionals working within the construction industry unless stated otherwise; while ‘experts’ refers to those interviewed for this research. A list of the professionals can be found in Appendix K.

- SuDS excludes sewage/black water and foul sewerage systems due to discharge restrictions (DEFRA, 2011)

7.1 Topics outside the scope of this dissertation:

- Consultation with the Environment Agency

- Biodiversity and wildlife

- Link between mental health and green spaces

- Pollution

- Constructed wetlands

- Consultation with the public

8.0 Literature Review

8.1 Introduction

This literature review aims to identify relevant academic studies, guidance manuals, and policy documents to understand the barriers to SuDS implementation in the UK. It will explore whether SuDS can be improved to better leverage professional expertise and optimise land use within development sites.

‘To those who understand the green infrastructure concept, and its promise, the need and opportunity to apply it in the pursuit of sustainability are quite profound.’

(Ahern, 2007 cited in Wright, 2011)

The reviewed literature includes scholarly papers and ‘grey’ literature, legislative and policy documents produced for disciplines including planning, landscape architecture, and construction. An example of the researchers’ Boolean Research technique is shown in Fig. 8 in Appendix L. Recommendations will focus on improving current processes and addressing gaps in research and resources. The review is organised under the following thematic headings:

- Theme 1 – Main Barriers to SuDS Implementation

- Theme 2 – Sustainability

- Theme 3 – Professional Skill Base and Perceptions

- Theme 4 – Adopters and Maintenance

- Theme 5 – Data Collection and Analysis

The literature identifies ambiguities in legislation and the design-to-build process, as well as perceived loopholes and weak enforcement of standards. These issues allow developers to meet planning requirements while potentially prioritising cost-saving solutions over optimal water management practices on and off-site. Furthermore, this review will explore the multiple definitions of Green Infrastructure (GI) and Sustainable Urban Drainage (SuDS) throughout the literature within the inclusion criteria. The full inclusion and exclusion criteria can be found in Table 8 Appendix G.

Moreover, this research will examine the feasibility of mitigating 1/100 through effective GBI design, ensuring no risk to buildings or infrastructure.

8.2 Theme 1- Main Barriers to SuDS Implementation

8.2.1 Policy and Legislation

8.2.1.1 Non-Statutory

The 2012 National Planning Policy Framework (NPPF) encourages prioritising developments with SuDs and highlights the importance of maintaining SuDS over their lifespan (UK Government, 2012). This framework promotes designing SuDS as central elements from the early stages of development.

Furthermore, the NPPF also recommends that ‘Local government policies should support appropriate measures to ensure the future resilience of communities and infrastructure to climate change impacts’ (UK Government, 2012). However, this document is non-statutory and uses non-obligatory language such as ‘should’ and ‘consider’.

In 2015, DEFRA issued a technical standards document for SuDS, offering concise design, maintenance, and operation standards to supplement the NPPF (DEFRA, 2015). Despite this, its non-mandatory status could reduce policy enforcement, affecting adherence to standards (Khanna, 2001).

The CIRIA SuDS Manual, developed with broad interprofessional stakeholder input, is widely regarded as a reliable guide for SuDS design and management (Woods Ballard et al., 2015). Its 2017 update introduced new content, requiring professionals to reference both manuals for complete guidance (Illman and Drake, 2017). However, the manuals are costly, creating a potential accessibility barrier for some professionals (White, 2005).

Furthermore, LASOO (2016) states the Non-Statutory Technical Standards for Sustainable Drainage: Practice Guidance, supports the technical standards used in conjunction with the NPPF and CIRIA SuDS Manual. Due to these documents age and poor ease of access, they may be overlooked.

The Cambridge SuDS Manual was developed specifically for the needs of the Cambridge Council. This document also helps resolve jurisdictional ambiguities when developments span multiple council boundaries. While less detailed than the CIRIA SuDS Manual, it offers concise information on costs, maintenance, and constraints, facilitating informed decision-making (Wilson et al., 2009). All the SuDS manuals aim to abide by the SuDS Principles represented in Fig 7 within Appendix I.

Other local councils have adapted the Cambridge Design and Adoption Guide rather than devising their own (Wilson et al., 2009). This comprehensive document defines SuDS, detailing their components and functions, making it both an informative resource and a practical design guide. This document references the CIRIA manual and follows its guidelines. Furthermore, emphasising that integrating the SuDS design into the development master plan at an early stage is paramount to a successful design, and this also requires early and effective consultation with all parties that are involved in the approval process (Wilson et al., 2009).

The Adoption Guides (Fig 9; Table 10) from the Cambridge Design and Adoption Guide can be found in Appendix M.

The Flood Risk Management and Funding document identifies that the responsibility of flooding was spread across many departments.

Figure 1 – The Funding Responsibility Flow Chart

Table 11, found in Appendix N, expands on the Funding Responsibility within the UK.

The complex structure of responsibility could identify possible ambiguity and confusion if professionals are unaware of this information (Burnett et al., 2024).

8.2.1.2 Statutory

The Flood and Water Management Act 2010 (FWMA) provides the statutory framework for flood management in England (DEFRA, 2017; UK Government, 2010). This act was deemed inadequate for addressing the UK’s flooding challenges (DEFRA, 2017). In contrast, the Welsh Government’s Schedule 3 establishes statutory regulations for surface water systems in new developments, using enforceable language such as ‘must’ and ‘require’. (Welsh Government, 2019). However, Schedule 3 and its accompanying guidance do not include any design or construction support. For this, the authors have forwarded readers to the non-statutory CIRIA manuals.

Similarly, the Scottish Government introduced a statutory policy framework in 2021 to create ‘Water-Resilient Places’, addressing fragmented decision-making processes (Scottish Government, 2021). However, the lack of explicit definitions for terms like ‘surface water’ and ‘water-resilient places’ and the use of unfamiliar terminology may create additional hurdles for professionals (Wright, 2011). The intention was to overcome issues created by the multiple influences in the decision-making process and the range of legislation and policies in place in Scotland (McLeod and Mickovski, 2024).

8.2.2 Cost

Cost remains one of the primary barriers to the widespread installation of SuDS, as identified in the literature. However, cost breakdowns in existing studies are often vague, leading to gaps in understanding and potential biases in decision-making. Many barriers to SuDS are perceived rather than substantiated, relying on assumptions or incomplete data (Cotterill and Bracken, 2020). This stresses the need for clear, evidence-based cost-benefit analyses to enable professionals to make informed decisions.

The Lasoo Non-Statutory Guidance emphasises that integrating SuDS into landscape design from the earliest stages of planning is more cost-effective, as it reduces time and costs associated with potential functional failures (LASOO, 2016). While the guidance outlines a systematic design sequence for achieving cost-effectiveness throughout a project’s lifecycle, it does not define cost parameters in detail, leaving room for misinterpretation (LASOO, 2016).

Similarly, Schedule 3 of the FWMA and its accompanying Sustainable Drainage Explanatory Memorandum (SDEM) focus primarily on design and installation costs, highlighting potential savings by avoiding the need to build or connect to traditional infrastructure (Welsh Government, 2018). However, the SDEM discusses maintenance costs only for the first year, which may be disproportionately represented, as maintenance is required over the system’s lifetime (Welsh Government, 2018).

McLeod and Mickovski (2024) highlight that the cost of building and maintaining a SuDS is a barrier for developers, suggesting that developers are looking to reduce construction costs with little concern for the long-term maintenance costs to the subsequent adopter. Conversely, adopters are primarily focused on the long-term performance of the system, with little concern for the initial investment made by developers.

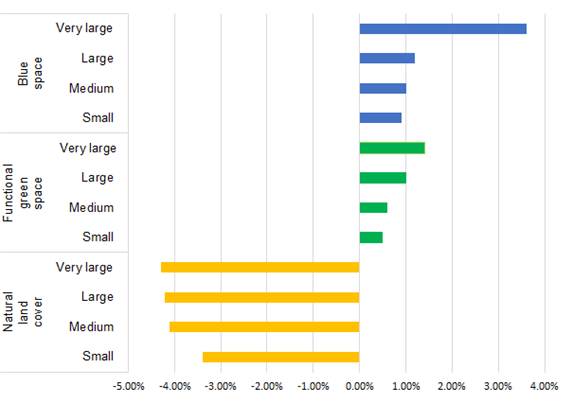

Despite these challenges, there is evidence that SuDS implementation can deliver economic benefits. Data from the Office of National Statistics (ONS) indicates that urban homes near parks, gardens, playing fields, and other publicly accessible green spaces command higher property values. For example, house prices can be up to £4,813 higher in proximity to green and blue spaces (Anderson and Vahe, 2018; Lorenzi, 2019). Fig 2 identifies the percentage increase in property value when dwellings depending on how close they are located.

Figure 2 – Percentage House Price Increase in relation to the distance from Blue and Green Spaces

(Anderson and Vahe, 2018)

Government funding also plays a critical role in SuDS adoption. In the Autumn Budget of 2024, the Labour Government allocated £2.4 billion for flood defences over 2024-2026 (Treasury, 2024). However, it acknowledged ‘significant funding pressures’, indicating that plans might require reassessment from 2025-26 (Treasury, 2024). Despite these constraints, the investment has the potential to reduce flood risk by 5-11% by 2027, saving the economy an estimated £2.7 billion (Burnett et al., 2024). This highlights the availability of public funds that could be leveraged to support SuDS integration in new developments, aligning with long-term economic and environmental goals.

8.3 Theme 2 – Sustainability

8.3.1 1 in 30 and 1 in 100-Year Storm Events

The Environment Agency (EA) outlines three annual probabilities used to define discharge compliance limits for weather events of varying frequencies:

- 100% (1 year),

- 3.33% (30 year) and

- 1% (100 year)

(Kellager, 2013)

DEFRA’s Preliminary Rainfall Runoff Management Document recommends that runoff up to the 1% annual probability event (1/100) should ideally be managed onsite using designated temporary storage areas unless it can be demonstrated that offsite discharge would not result in nuisance, damage, or increased river flows during flooding (Kellager, 2013). However, the use of the term ‘preferably’ creates ambiguity, as it implies this standard is not compulsory. Such language allows for flexibility in interpretation, which may undermine consistent implementation.

The National Standards for Sustainable Drainage Systems explicitly state that discharge flow rates from development sites must not exceed pre-development levels during both 1 in 1-year (1/1) and 1 in 100-year (1/100) storm events (DEFRA, 2011). Additionally, drainage systems should be designed to prevent flooding:

- On any part of the site for a 1 in 30-year rainfall event; and

- During a 1 in 100-year rainfall event in any part of: a building (including a basement); or utility plant susceptible to water (e.g. pumping station or electricity substation); or

- On neighbouring sites during a 1 in 100-year rainfall event.

(DEFRA, 2011)

These standards suggest that designers can adapt GI and SuDS techniques to withstand 1/100 storm events, particularly in areas designated for flood management, ensuring hard infrastructure remains unaffected.

8.4 Theme 3 – Professional Skill Base and Perceptions

8.4.1 Language and Terminology

Confusion arises from the varying and often inconsistent definitions of GI and SuDS across policies and literature (Wright, 2011). The literature highlights that although these terms are sometimes used interchangeably, they are distinct. GI refers broadly to networks of natural and semi-natural features that provide environmental, social, and economic benefits, whereas SuDS specifically relate to managing surface water sustainably.

The table below is an excerpt from the full Table 1 – GI and SuDS Definitions found in Appendix D.

Table 1 – GI and SuDS Definitions

| GI | European Commission, 2024 | ‘A strategically planned network of natural and semi-natural areas with other environmental features, designed and managed to deliver a wide range of ecosystem services, while also enhancing biodiversity.’ | Purpose/Function/ Components |

| SUDS | CIRIA Suds Manual, 2015 | Sustainable drainage systems (SuDS) give equal consideration to controlling water quantity, improving water quality, providing opportunities for amenity and improving biodiversity. Similar to a natural catchment, a combination of drainage features (also known as components) work together in sequence to form a management train. | Purpose/Function/ Components |

For example, the NPPF uses the term ‘green space’ without providing a clear definition, leading to ambiguity. In contrast, the European Commission’s definition of GI is explicit, detailing its purpose, function, and components with minimal ambiguity (European Commission, 2024). This variability in definitions reflects the need for flexibility to account for differing topographies, scales, and flood risks but can also confuse professionals who require clarity in purpose, function, and mechanism (Wright, 2011).

Subjective terms such as ‘contribute’ and ‘enhancement’ in definitions further complicate understanding (Benedict and McMahon, 2006; LGA, no date). Ambiguity in statutory definitions, such as that within Schedule 3, leaves room for contention, as it broadly describes SuDS functions post-installation but does not specify required system components. This lack of detail can hinder enforcement and the establishment of professional standards.

By contrast, the CIRIA SuDS Manual offers a concise, clear definition, explaining the concept, process, function, and components of SuDS. This approach minimises contention and ambiguity, providing a reliable reference for professionals. Furthermore, Pamukcu-Albers et al., (2021) highlighted that increasing awareness, knowledge and skill base will improve the planning, design, installation and maintenance of SuDS.

8.5 Theme 4 – Adopters and Maintenance

8.5.1 Maintenance, adoption and management

The maintenance, adoption, and management of SuDS post-construction are highly debated topics within the literature. Statutory and non-statutory guidance, including the CIRIA SuDS Manual, emphasises the necessity of comprehensive maintenance plans (Woods Ballard et al., 2015). The NPPF also mandates that SuDS must include maintenance arrangements to ensure their functionality throughout the development’s lifetime (UK Government, 2012). Similarly, the CIRIA guidance stresses that the purpose of a maintenance plan is to ensure all those involved in the maintenance and ongoing operation of the SuDS system understand its functionality and maintenance requirements in terms of supporting long-term performance to the design criteria to which it was designed (CIRIA, 2021). These guidelines collectively highlight the critical role of maintenance in ensuring the lifelong health and performance of SuDS.

DEFRA’s national standards for SuDS identify that an approved drainage plan must include the safe operation and maintenance of SuDS (DEFRA, 2011). However, this document does not state for how long a maintenance plan should be in place, which could be misconstrued as ambiguous.

Research reveals that 70-75% of Local planning authorities (LPAs) have no monitoring or reporting of SuDS (Welsh Government, 2018). Many LPAs report constraints in time, expertise, and resources, which hinder their ability to ensure that maintenance arrangements are implemented and adhered to for the lifetime of the development (Welsh Government, 2018).

The CIRIA SuDS Manual provides detailed operational and maintenance requirements for each SuDS component (Woods Ballard et al., 2015). An example of one of these maintenance requirements is in Table 12 of within Appendix O.

This is echoed within the Anglian Water SuDS Manual (Anglian Water, 2023). Furthermore, Susdrain emphasises the importance of maintenance through their literature and online resources (CIRIA, 2021).

A table of recommendations by Charlesworth and Booth (2016) below in Fig. 3 informs on SuDS maintenance Standards.

Low Visibility Sites

Low: Basic maintenance to ensure function

Low frequency visits

Main litter removal and maintenance of vegetation

Additional activities may be identified to improve operations

High visibility sites

Medium: For function and aesthetic appeal

More frequent visits

Urban area, public community spaces and densely populated areas

High: Enhanced maintenance

Additional focus on planting specification and aesthetic appeal

Figure 3 – SuDS Maintenance Standards

(Charlesworth and Booth, 2017, p.51)

Due to the adoption restrictions detailed in Table 14, Appendix Q. The Cambridge City Council SuDS Manual stipulates that SuDS located within curtilage or private land will not be adopted by Local Authorities, leaving maintenance responsibilities to the property owner (Wilson et al., 2009). A study by McLeod and Mickovski (2024) found that 83.3% of homeowners were unaware of the maintenance requirements for SuDS features within their property boundaries. This lack of knowledge and the failure of the developers to pass on relevant SuDS information and instructional material to the vendors. Furthermore, this lack of information further contributes to a negative attitude towards SuDS and the discrepancies among professionals regarding flood protection and water quality enhancement (McLeod and Mickovski, 2024).

8.6 Theme 5 – Data Collection and Analysis

8.6.1 Data

There is insufficient research to determine the software that could best utilise SuDS to aid professionals when designing and implementing SuDS.

8.6.2 Urban Creep

A study by Mcdonnell and Motta (2021) suggested that before 2003 urban creep was calculated at an average of 7.55% across the lifetime of a property. This increase in impervious materials was shown to directly correlate with an equivalent rise in runoff volume; for instance, a 10% increase in impervious material resulted in a 9.9% increase in applied precipitation runoff (Mcdonnell and Motta, 2021). Suburban areas accounted for 67% of the total increase in impervious surface, identifying that higher-density areas are more likely to have urban creep than other areas (Mcdonnell and Motta, 2021). These findings highlight a lack of public awareness regarding the importance of maintaining SuDS components within property boundaries. However, more recent urban creep statistics remain unavailable, creating a knowledge gap in understanding of its current impact (Tewkesbury, 2019).

8.7 Literature Review Conclusion

The literature highlights several persistent barriers to SuDS implementation, including costs, knowledge gaps, limited understanding, maintenance challenges, adoption issues, insufficient funding, and the overwhelming number of statutory and non-statutory reference documents. Despite ongoing efforts to address these issues through new and updated guidance, significant obstacles remain (White, 2005; Schlüter and Jefferies, 2005). Inconsistent definitions and terminology exacerbate confusion, creating potential ambiguity and contention throughout the construction and maintenance phases. The lack of standardisation and non-statutory nature of most of the documents have compounded these barriers. The literature identifies that the CIRIA SuDS Manuals are well-informed and respected within the industry. Additionally, showing long-term maintenance and management plans are crucial to prevent SuDS systems from failing. Without proper maintenance, SuDS systems risk becoming redundant, undermining their principles and purpose. Furthermore, without proper funding for Local Authorities to carry out any maintenance beyond the developer’s responsibility, the validity of the SuDS principles and purpose will be in jeopardy. Costs include both the initial outlay, and the ongoing maintenance; professionals should consider the added value SuDS contribute to surrounding properties, which positively impacts ROI. Therefore, comprehensive calculations show that SuDS are cost-effective despite their many variables. Despite these barriers, the literature demonstrates that SuDS remain a cost-effective and innovative solution for managing water sustainably.

There is sufficient data to guide professionals on how to successfully mitigate a 1/100 giving the opportunity for professionals to create innovative spaces that can accommodate these events despite site-specific variables, including geology and infiltration rates. This literature supports the integration of SuDS within GI frameworks to create multifunctional spaces that balance flood mitigation, water quality improvement, and urban resilience.

9.0 Methodology

9.1 Introduction

This chapter identifies the research methods for investigating whether construction professionals offer creative and innovative approaches to integrating SuDS into GI in residential developments. Furthermore, how GI can be optimised to address increased flooding and storm events, and how future systems can be designed to overcome these challenges.

9.2 Research Theoretical Framework

The researcher’s professional experience suggests that unclear guidance, limited incentives, and insufficient policy enforcement hinder the development of creative and integrated SuDS solutions. As a result, developers often opt for the simplest and most cost-effective engineered solutions. The widely used CIRIA SuDS Manual, a non-statutory guidance document for engineered SuDS solutions (Woods Ballard et al., 2015), allows the flexibility of interpretation, with professionals often favouring straightforward approaches. Potentially the SuDS designs, while economical at the time of implementation, may not account for climatic, geological, or topographical changes.

This research theoretical framework suggests that future-focused schemes integrating SuDS components into a more strategic cohesive GBI management train can safely manage and hold all surface water within the SuDS GI, during a 1-in-100-year storm event, provided the infrastructure is strategically designed. This research aims to test this theory. The research methods are shown in Table 2 below.

Table 2 – Research Methods

| Research Method | Type | Method | Analysis |

| Literature Review | Secondary | Qualitative | Thematic |

| Interviews | Primary | Qualitative | Thematic |

| Quantitive |

9.3 Research Design

To explore the theoretical framework a combination of qualitative and quantitative methods, including a detailed literature review and ten semi-structured online interviews with industry professionals.

From the information found from the literature review, the research data will be collated from highlighted key topics to themes, as depicted in the table below. This is to aid in streamlining research with thematic analysis.

Table 3 – Thematic Coding

| Topic Coded Data | Themes | Topic Coded Data | Themes | |

| Policy and legislation | Theme 1- Main Barriers to SuDS Implementation | Knowledge, Skill base, Training | Theme 3-Professional Skill Base and Perceptions | |

| Costs and economic benefits of SuDS | Language, Terminology | |||

| CIRIA and other SuDs Manuals | Positives | |||

| Risk aversion | Process | |||

| Developers | Correct methods | |||

| Challenges and Barriers with SuDS | Precedents | |||

| SuDS components | Recommendations | |||

| Climate change | Maintenance | Theme 4-Adopters and Maintenance | ||

| Sustainability | Community engagement | |||

| 100-year storm events | Theme 2- Sustainability | Councils and Local Authority | ||

| Future-proofing | Public perception | |||

| Flooding | Data analysis | Theme 5 – Data Collection and Analysis | ||

| Drought | Flood risk | |||

| Soil quality | ||||

| Urban creep | ||||

| Infiltration | ||||

| Landscape design | ||||

| Sacrificial areas |

9.4 Sampling and Data Collection

Phenomenological research design will be used to gain a deeper understanding of industry perspectives, procedures, emotions, and behaviours. Open-ended interview questions will provide rich data for thematic analysis.

Descriptive research will systematically examine existing standards, expert opinions, behaviours, and strategies. This approach focuses on:

- The rationale behind current design and engineering practices.

- The role of landscape architects and other professionals in SuDS integration.

- Policy mechanisms that enable or hinder enforcement.

- Evaluating whether hidden flood management improves new housing developments.

- Assessing cost implications for developers and buyers resulting from enhanced amenities.

This research approach ensures a comprehensive understanding by combining multifaceted expert insights with systematically gathered unaltered, descriptive data (Lim, 2024).

Data will be gathered via semi-structured online interviews, reducing travel costs and increasing accessibility. Interviews will be conducted one-on-one via Teams or Zoom over a two-week period. This format was selected in place of written or emailed surveys to allow for follow-up and clarifying questions, enabling richer insights that might not have emerged otherwise. This approach enables participation from the researcher and experts who might otherwise face scheduling constraints (Winstanley, 2012). The interviews are restricted to a specific time window to emphasise their importance and reduce scheduling conflicts. experts will respond to structured, industry-specific questions designed to facilitate comparative analysis across sectors and gather targeted data.

Open-ended questions will encourage detailed responses, providing deeper interpretations of the participants’ reasoning. Interviews will be recorded and transcribed using Google software, with transcripts manually coded to identify themes such as those within the study by Parameswaran, Ozawa-Kirk and Latendresse (2020).

9.5 Sampling Strategy

Participants will be drawn from various professional disciplines involved in SuDS design and construction, including project managers, landscape architects, engineers, government officials, SuDS product specialists, and developers. This sampling ensures a broad perspective on ‘real-world’ practices and challenges in SuDS implementation within new developments.

9.6 Data Analysis Techniques

Collected data will be thematically coded as shown in Table 3. The qualitative data will be converted into quantitative data. The quantitative data will be visually represented through tables and graphs to illustrate key findings.

Themes will be identified through:

- Coding surface-level responses.

- Grouping codes with shared similarities into broader themes.

- Tables will present this data to enhance transparency and support confirmability

(Anfara, Brown and Mangione, 2002)

A pilot study was explored to inform adjustments to the length and content of interview questions to ensure they align with participant availability and provide meaningful insights.

Table 13 In Appendix O identifies the coded themes that answer the research objectives.

9.7 Mitigating ethical issues:

Ethical standards of research require that all participant information be deidentified, using participant identification numbers for each participant ensuring confidentiality through participant identification numbers or pseudonyms (Blignault and Ritchie, 2009).

An initial email will invite experts to participate, detailing the purpose of the research, ensuring anonymity, and informing them of their right to redact or withdraw data at any point before publication. The email of request is available to view in Appendix A.

Before starting the interview, participants will be asked to confirm their willingness to proceed and be reminded of their right to withdraw. Any identifiable information, such as names, will be redacted from the recording transcript to maintain confidentiality.

9.8 Possible Constraints

Potential constraints include:

- Non-responses to interview invitations could narrow the data available and introduce potential industry bias.

- Withdrawal of data or redactions, which may reduce the volume of information available for analysis.

10.0 Results

10.1 Introduction

In this chapter, the primary data collected will be used to discuss and compare the one-to-one interviews to identify the barriers that the experts state are inhibitory towards more effective and efficient SuDS design and installation. This will be organised thematically with quantitative graphs to aid understanding of the data. The number of experts who contributed to which theme is found in Table 7 in Appendix F.

The six participants had different occupation expertise and are listed in the table below.

Table 4 – Participant Occupation Expertise

| Participant ID | Industry occupation title |

| P1 | Landscape Architect specialising in SUD |

| P2 | Suds System business specialist |

| P3 | Senior advisor for Sustainable Drainage |

| P4 | Project Manager, Environmental Site Design |

| P5 | Director at a company specialising in improving SUDs and reducing pollution |

| P6 | Civil engineer specialising in environmental Water Management |

Some comments made by the participants were industry sensitive. This information was attributed as ‘Anonymous’ and therefore allowed by the participants to be included in the research.

The percentage of experts contributing to a specific barrier identification is identified in Table 5 below.

Table 5 – Participant Barrier Contribution

| Main Barriers to SuDS implementation | Contributions are shown as a percentage |

| Lack of understanding: Lost/Skills/Knowledge/Adoption/Insurability/Design | 100 |

| Legislation- confusing and conflicting | 100 |

| Land Price | 33 |

| Developers doing what they want | 50 |

| Government | 50 |

| No interprofessional integration | 83 |

| Maintenance | 100 |

| No trust in property owners | 67 |

| Soil, infiltration and topography factors | 67 |

This data has been transferred into a bar chart to identify the number of experts speaking about the specific barriers below.

10.2 Theme 1: Main Barriers to SuDS Implementation

The data has identified that the experts state there is a lack of understanding of SuDS throughout the industry sectors as well as legislation and maintenance. it was apparent to the researcher that these were contentious topics which raised much debate during some interviews.

10.2.1 Legislation

The experts unanimously agreed that there are too many legislative obstacles and barriers hindering SuDS design and development. “The UK keeps making it more and more complicated. In the USA, it’s simple and easy to understand, and they’re more respected.” (P1). There was consensus that England missed an opportunity to utilise the statutory Schedule 3 legislation, but they “wait in the hope that this will be adapted and incorporated into English Policy soon” (P5). Furthermore, there was an emphasis by all the experts that the legislation needs to be regulated to make SuDS and GI common practice: “I think it’s that the relationship is about the relative benefits and design priority, creating a successful process requires partnership working with clear governance and a memorandum of agreement” (P4). It was highlighted that currently, there are legal blockages within the water industry, where water companies are not allowed to provide non-potable water to residential properties. This consequently blocks any SuDS components using rainwater capture reuse mechanisms; however, “OFWAT is trying to get this removed” (P5). Unfortunately, the current UK government has postponed the discussion of implementing Schedule 3 in England, stating a higher priority on building targets over ensuring they do not flood (P3).

10.2.2 Developers

The experts posit that generally, developers prefer to only work within the current legislation, policy and regulations. P4 suggested that “the more promoted these [SuDS] systems are, the more positively they will respond”. There was an attitude by 50% of the experts that developers disregard legislation “Developers ignore the legislation, even with Schedule 3” (P3). However, the legislation in England is not statutory, and the behaviours of the professionals were “obstinate and ambivalent” (Anonymous). Interpersonal communication and relations need to be improved, as expressed by 83% of the experts. Working independently is not conducive to intricate design processes; “there could be more collaboration and better understanding across the industry” (P5).

10.2.3 Cost

There was ambiguity and contention over the precise meaning of cost with regard to SuDS initial outlay and ongoing maintenance. However, the experts were all in consensus that the total cost of installation throughout a development’s lifetime is cheaper than that of standard piped drainage systems. “We have managed to save the client a significant amount of money by installing blue-green roofs […] I think the client did the costs, and it was cheaper to put blue-green roofs on the majority of the blocks as opposed to building an attenuation tank of a similar volume. So, then you free up your landscape space on the ground to be much more flexible” (P1). SuDS and GI aid in the increase of amenity value, which will encourage the sale of properties as well as increase the prices in the area (P5); furthermore “GI and SUDS will absolutely help sell your property and for more money!” (P2). However, it was mentioned that to minimise the costs, SuDS must be considered from the start of the planning and design process, and adequate testing must be completed: “You can maximise your profits by designing in the right way” (P3).

Half of the experts commented directly about the main UK Government; this was in part due to the sensitive nature of the topic and possible stakeholder conflict of interest. The delay in Schedule 3 implementation in England was due to “an increase in the time and funding for building dwellings and hitting building targets” (P3).

10.3 Theme 2: Sustainability

10.3.1 SuDS

All experts believed that SuDS and drainage should be linked together. Altering the perception of SuDS to critical infrastructure will be “respected throughout the lifetime of the system” (P6). “When using the term infrastructure, it creates a critical need.” (P1).

However, there were contrasting views on what data to collect in order to design effectively for SuDS. Some experts were of the opinion that a site’s drainage taken in isolation was adequate. Additionally, the majority discussed the need for a more holistic approach to not only avoid any negative impacts downstream but also to understand the significance of potential flood risks upstream (P4; P5). Moreover, two experts believed if adjacent developments linked their SuDS/drainage network, it would help balance any surface water discrepancies, whether in times of drought or heavy rainfall (P2; P5).

Although attenuation ponds are simple and “do the job” (P2), if there were a large storm event, the pond may not be able to cope; therefore, with more integrated components, this would increase the surface area and volume capacity to absorb water (P3).

10.3.2 Drought

Three of the experts stated that drought must be taken into consideration, “Some councils do consider drought, but it is not common” (P1). With almost too much emphasis on the infiltration rate (P3; P4), little is done to mitigate drought; there are many innovative materials like “Rockwool and perma-void, which have 90% void space and significant wicking effects” (P1).

10.4 Theme 3: Professional Skill Base and Perceptions

10.4.1 Knowledge/Perspectives

All the experts believed that there are large skills gaps across all industries, such as SuDS design and management. P3 highlights that many professionals perceive SuDS as “obstacles rather than opportunities”. “Developers, designers and engineers don’t understand some SuDS and the calculations for them. They request the wrong stuff which wastes time and resources” (P5). However, P2 stressed that “Green infrastructure data is fluid and, therefore, hard to answer engineering calculation needs”.

10.4.2 Terminology

Terminology was a contentious subject for the majority of experts. Each profession “tends to be siloed and they have their own language, and they have their concepts and their training” (P4). This creates segregation between the industries when terminology needs to be more cohesive (P5). Furthermore, the definitions of GI, GBI and SuDS are “ineffective in creating an integrated natural SuDS” (P3). P1 stated, “A plastic tank underground is still classed as sustainable”.

10.4.3 Design

It was identified that “often, a lot of schemes are paved; this ensures there are low maintenance costs and more chance of adoption” (P1). Nonetheless, this is perceived as a “lazy design, being cheap and easy to produce” (P3). “Living sustainable drainage systems can be attractive and you don’t need to hide them” P4.

10.5 Theme 4: Adopters and Maintenance

10.5.1 Maintenance

The experts’ consensus is that maintenance of landscaping is inadequate due to lack of funding, change of governments, and poor specialist knowledge of SuDS. There is insufficient interest by the Local Authorities, main adopters and developers in ensuring that maintenance is carried out after the developers’ responsibilities end; “Local Authorities are just so risk averse” (P1). The experts emphasised that if the SuDS are not maintained, they are likely to become functionally redundant; “So many SuDS are now failing because they are not looked after, it is only a matter of time before they stop altogether” (P5).

However, participants mention varying methods to ensure maintenance is achieved, including the employment of a maintenance company passing a charge to the property owners (P2) and adding deed restrictions and requirements (P3; P6). All participants asserted it is essential to be in conversation with the authorities who will be adopting the space. Furthermore, the main adopters be consulted from the beginning of a design to ensure that what is produced will be looked after post-handover (P1; P6). “There is no point in building them in the first place if they will not be looked after once the maintenance plans are over” (P5). Four of the experts emphasised that if landscapes were maintained correctly, SuDs and surrounding GI would have the potential to retain more water volume. The experts argued failure to maintain SuDS was due to the lack of resources, staff, knowledge and equipment available to carry out unconventional work practices.

10.6 Theme 5: Data Collection and Analysis

10.6.1 Data

From the interviews, there were mixed opinions about the climate change and year-storm events data available; two experts said it was outdated, whilst one believed it was updated regularly. However, 67% believed that the industry does not design developments for more severe storm events or far enough into the future.

All the experts stated that if there are many components within a designed SuDS management train, then it is feasible to hold 1/100 volume without affecting any hard infrastructure. However, further investigation would need to be done to account for topography and geology (P6).

It was highlighted by 50% of the experts that water storage calculations are conservative due to the assumption that all water storage vessels (including water butts) are deemed full, and the volume data taken for infiltration and evapotranspiration are at base level (P6). Furthermore, the lead local flood authority (NHBC) does not consider the soil voids; therefore, “designs should cope with bigger storms than they are designed for” (P2).

10.6.2 Urban Creep

The experts confirmed that the industry estimates 10% urban creep in surface water drainage calculations. However, there was disagreement among the experts regarding deed restrictions to inhibit adaptions to drives and within curtilage SuDS, therefore preventing urban creep. P5 felt a deed restriction would be a simple way to resolve this issue. However, P3 suggested that due to a lack of resources within the local governments, these would become unenforceable. P3 further explained that urban creep was increasing due to the change in EV charging needs within curtilage from residents converting front gardens to driveways.

10.6.3 Limitations

Despite the methodological limitations of a developer and planner failing to respond to an interview request, this study met the research objectives whilst highlighting the difficulties with the legislation and manual guidance. The initial interview questions lacked sufficient focus on landscape-designed areas, prompting the researcher to use follow-up questions to gather relevant information. The research subject was quite broad, creating multiple themes and topics. Consequently, some data of lesser significance was omitted to align with the constraints of the dissertation.

10.7 Conclusion

The interview results reveal several barriers to designing and implementing SuDS in developments, with the primary challenges being a lack of understanding, maintenance issues, and inadequate legislation. These barriers have persisted over time, and without effective changes in legislation, public perception, and enhanced professionals’ skill base, they are likely to continue. The experts emphasised that it is possible to mitigate a 1/100 through a well-designed SuDS management train integrated into a cohesive GI design without compromising buildings, hard landscapes and infrastructure.

11.0 Discussion

11.1 Introduction

By comparing and contrasting the data from the pertinent literature and expert interviews, it was possible to evaluate and analyse the key outcomes. The study demonstrates a correlation between the legislative barriers alongside public and professional perception with the lack of SuDS and GI innovative design and incapacity to mitigate for a 1/100, aligning with the research framework theory. Table 6 below concisely identifies the barriers and what will be considered throughout this discussion.

Table 6 – Barriers Considered Throughout the Discussion

| Theme 1 | Statutory Legislation and Policy Issues Local council and authorities’ adoption / versus management companies. Differences between England / Wales (e.g., Schedule 3 in Wales) Lack of clear enforcement policies for SuDS adoption and maintenance in England. Advocating for statutory legislation and dedicated maintenance bodies to ensure functionality and respect. | ||

| Economic Implications SuDS is a cost-effective solution for enhancing property value and amenities. Misconceptions about high installation costs. Potential solutions. | |||

| Theme 2 and 5 | Design and Technology opportunities Multi-functional space Integrate with green infrastructure. Advanced design to meet resilience goals. Implications of Urban Creep. | ||

| Theme 3 | Public and Professional Awareness Homeowner awareness and knowledge about SuDS and their maintenance responsibilities. Opportunities to educate stakeholders, improve public perception, and enhance system adoption. Role of Interprofessional Collaboration. Reframing SuDS as critical infrastructure, equivalent to utilities like water and electricity. | ||

| Theme 4 | Maintenance Challenges Barriers to SuDS maintenance. Alternative maintenance needs compared to standard drainage systems. Consequences of poor maintenance. | ||

| Challenges to broader implementation Devising a strategy to educate the public and professionals. Government priorities towards collaborative working partnerships. Government focus on land-use and GBI strategy to align with long-term flood mitigation with home building targets. Strategy to change awareness of maintenance requirements |

11.2 Legislation, Manual and Guidance

Both the literature review and experts emphasise the inconsistencies in statutory and non-statutory frameworks across England and Wales, creating contention in the design and build process (Burnett et al., 2024). The absence of Schedule 3 in England has allowed for subjectivity within the non-statutory legislation resulting in cost-driven compromises and inconsistent implementation (DEFRA, 2017). Ultimately, the responsibility for legislation is held by the Central UK Government, and until clear policies are implemented and legal blockages removed, these barriers will persist (Burnett et al., 2024).

Building on the respect for the CIRIA SuDS Manual as seen from the literature and experts, an adaptation of this document, utilising the contributing stakeholders and the UK government advisory bodies, could improve consistency by providing standardised definitions and terminology. Adapting the guidance manual could fostering collaboration and advance knowledge (Benedict and McMahon, 2006). Furthermore, this would aid in the continuity of projects and ease of regulation (Wilson et al., 2009). Legislative change creates potential for a straightforward recognised system of approach to the design process.

The viability to mitigate for 1/100 has potential under current NPPF legislation which already recommends such designs (UK Government, 2012). Minor changes in this legislation could encourage the protection of such standards and enhance innovative designs by landscape architects and engineers, enhancing stormwater capacity and usability of GI spaces (Charlesworth and Booth, 2016). Betterment of designs could also increase awareness of sustainable urban draining and the likelihood of maintenance, ensuring long-term functionality (Cotterill and Bracken, 2020). Furthermore, there could be potential for these 1/100 mitigated sites to attain water from neighbouring sites; however, the literature does not explore practical, innovative design strategies for mitigating 1/100 which is an obvious gap in industry resources.

11.3 Cost

The cost-effectiveness of SuDS remains a contentious issue, as highlighted in both the literature and interview data. The costing data is often assumed or incomplete (Cotterill and Bracken, 2020). Developing a standardised costing protocol, which incorporates initial site testing, installation, and ongoing maintenance, could improve clarity and enable accurate ROI calculations. While this would be a time-intensive process due to variables in design, geology, and topography, creating a software model to systemise cost estimations could address this challenge. Understanding the true cost of SuDS is crucial to revealing economic incentives and higher profit margins, as well as recognising the increased amenity value linked to green and blue spaces (Waddington, 2023). However, with increased amenity values comes the potential for gentrification and reduced affordability for certain demographics (Finio, 2022). Without addressing the misconceptions and misrepresentation of SuDS costs, economic uncertainty will remain a major barrier to their adoption. Furthermore, this could reduce the ability for innovative design.

Reframing SuDS as an asset of critical infrastructure similar to utilities such as gas and water could encourage integration into standard practice and help overcome professional hesitations (IBM, 2024). Statutory legislation, similar to Schedule 3, could shift perceptions and expand the professional skill base through training and education to update industry knowledge (McLeod and Mickovski, 2024). Subsequently, this could encourage the expansion of the professional skill base, allowing for more education and up-to-date knowledge within the industry. This could support the new positive impression and reduce any potential stigma still associated with SuDS (White, 2005; Cotterill and Bracken, 2020).

The discrepancy of opinion between the developers and the adopter supports the research theory that developers often choose basic SuDS solutions, neglecting opportunities for sustainable designs aligned with the CIRIA SuDS Manual or the NPPF principles (McLeod and Mickovski, 2024). Early clarification of post-build responsibilities could mitigate this providing a clean model of long-term responsibility (Wilson et al., 2009; McLeod and Mickovski, 2024). Adopting statutory legislation similar to Schedule 3 in Wales, which establishes SuDS Approval Bodies (SABs), could standardise responsibilities and reduce maintenance-related failures (Welsh Government, 2018). Without clear long-term accountability, SuDS risk becoming redundant due to inadequate post-construction maintenance, further undermining their critical status among professionals.

11.4 Maintenance

The maintenance of SuDS emerged as a critical challenge from both the literature and expert interviews with joint consensus that the unexpected maintenance responsibilities include poor planning, funding gaps, insufficient knowledge, awareness and expertise (Charlesworth and Booth 2016). Unlike traditional systems, SuDS lack a clear line of responsibility for ongoing maintenance and financial obligations, exacerbating uncertainty (LASOO, 2016). Legislation similar to Schedule 3 in Wales, which mandates maintenance plans and accountability through SABs, could provide a structured framework to aid in overcoming these barriers (Welsh Government, 2018). This would also address knowledge gaps, support homeowner responsibilities for in-curtilage systems, and prevent developers from evading accountability (McLeod and Mickovski, 2024). Placing responsibility on uninformed homeowners without adequate support or resources could be considered negligence on the part of developers (Posner, 1972).

The perception of SuDS as a non-critical infrastructure diminishes their prioritisation compared to utilities (IBM, 2024). This perception is problematic, as SuDS are essential for mitigating flood risks, enhancing amenities, and increasing property and amenity values (Waddington, 2023). Without a paradigm shift to classify SuDS as critical infrastructure, they risk being dismissed as greenwashing rather than functional solutions (Schlüter and Jefferies, 2005). At present, poor maintenance has contributed to inefficiencies (Burnett et al., 2024). Inadequate resources among Local Authorities further compound this issue, necessitating statutory policies to ensure maintenance plans are implemented and systems remain operational (Welsh Government, 2018). Moreover, the change in policy could aid an education and recruitment drive to address the lack of specialised tradespeople (Burnett et al., 2024).

Educational initiatives and recruitment efforts are also needed to build a skilled workforce capable of maintaining SuDS. Legal and insurance implications pose additional challenges; for example, flooding caused by private SuDS systems could lead to disputes, and insurers often hesitate to provide coverage due to a limited understanding of these systems (Wright, 2011). Clear communication and collaboration between professionals and homeowners could empower individuals to maintain their systems, mirroring the responsibility expected for utilities; furthermore, improve the planning, design, installation and maintenance of SuDS (Pamukcu-Albers et al., 2021).

To address these challenges, the SuDS specialist Landscape Architect (P1) argued there is a need for a paradigm shift in how SuDS are perceived and managed. A suggestion by the Director specialising in SuDS improvement (P5) was that property and grounds management companies could offer a viable solution, providing ongoing maintenance in exchange for a service charge parallel to standing charges for gas and water. These companies could help to avoid issues found where Local Authorities are unable to enforce any deed restriction breaches due to lack of resources. Furthermore, grounds management and maintenance may aid in raising public awareness of urban creep (Mcdonnell and Motta, 2021). However, these charges may not be well received by the new vendors, and potential liability issues could remain if the adopting maintenance company were to go bankrupt.

In Wales, Schedule 3 and SABs have improved SuDS adoption and maintenance outcomes (DEFRA, 2017). Conversely, England’s delay in adopting Schedule 3 could lead to future challenges as developments face increasing weather intensity (Seneviratne et al., 2021). The legal responsibility of flooding is spread across many departments and institutions (see Fig. 1); opportunities could exist by consolidating this within a new statutory framework (Burnett et al., 2024). Furthermore, funding for flood prevention, as outlined in Appendix N, could be leveraged to support local governments in maintaining SuDS and incentivising developers with grants. Despite the availability of resources, for example, Central Government funding, inconsistent implementation highlights the need for better policy, the policies regulation and enforcement to ensure maintenance and accountability.

11.5 Conclusion

Undoubtedly, the discussion of SuDS and GI has revealed substantial barriers to their widespread adoption and long-term functionality. The cost of SuDS from different perspectives is often assumed and potentially incomplete, and insufficient planning test data collection have resulted in negative perceptions, while the lack of standardised costing strategies weakens accurate ROI. Addressing these issues requires a systematic approach, with early implementation of SuDS, including the input of statutory legislation to establish SuDS as critical infrastructure and improve interprofessional relations (Cotterill and Bracken, 2020). This would not only improve SuDS perceptions but also aid in the innovation of designs.

While the literature provides theoretical frameworks and technical guidance, the expert interviews highlight practical barriers. However, the literature neither fully resolves issues of urban creep nor offers concrete strategies for widespread public and professional education, which are critical to fostering collaboration and long-term adoption. Statutory legislation similar to Schedule 3 could resolve the ambiguities around maintenance responsibilities by integrating long-term maintenance plans within the regulatory framework. Furthermore, this could improve homeowner accountability, alleviate liability concerns and support Local Authorities with the addition of SABs.

To overcome inconsistencies between statutory and non-statutory legislation, the facilitation of new legislative reforms and up-to-date guidance is essential. Adapting the 1/100 NPPF guidance could encourage the innovative development of integrated SuDS-GI designs, thus improving flow mitigation whilst providing multi-functional spaces.

12.0 Conclusion

This research set out to explore how SuDS and GI can be innovatively integrated into new residential developments to mitigate the increasing frequency of 1/100 flood events. The findings highlight the complex challenges involved in the acceptance of SuDS into mainstream infrastructure, including economic contention, inconsistencies in legislative and policy frameworks, together with unresolved maintenance and adoption responsibilities. Despite the well-documented cost-effectiveness and amenity-enhancing potential of SuDS, misconceptions by developers and funding and skill resource constraints within local governments continue to hinder their widespread adoption. Early integration, site-appropriate testing, and encouraging interprofessional collaboration emerged as essential steps to optimise their implementation.

Maintenance remains a critical barrier to the effectiveness of SuDS. Addressing gaps in technical skills among professionals, increasing public awareness, and reframing SuDS as critical infrastructure akin to other utilities could help overcome engineering barriers and negative perceptions. Clear post-build adoption frameworks, supported by maintenance companies or service charges, are vital for ensuring long-term functionality. Enhanced funding mechanisms and grants for developers could further incentivise adherence to these systems. To better understand the implications of these results, future studies could address how to design an extensive integrated SuDS-GI system between various developments. Without clear and enforceable processes, the current contention and ambiguity within the industry will continue to impede progress, making maintenance a persistent constraint on SuDS long-term success.

Legislation remains a critical area for improvement, as inconsistencies and ambiguities in statutory and non-statutory documents perpetuate existing barriers. The missed opportunity to implement Schedule 3 in England highlights the need for a unified approach parallel to the successful models seen in Wales. Developing comprehensive statutory guidance to complement existing legislation could provide clarity, reduce contention, and promote accountability. Further research is required to clarify accountability and legal implications for failures and to establish a robust framework for prosecution when necessary. More importantly, amending the Flood and Water Management Act 2010 to enforce statutory legislation across all phases of SuDS development, testing, planning, design, installation, maintenance, and adoption, would establish mandatory standards and regulate the industry more effectively.

The research supported the theoretical framework that developers often opt for simplified SuDS solutions driven by perceived cost savings, inadequate statutory legislation, and limited industry awareness. While the results identify barriers and opportunities, a detailed exploration could highlight detailed processes to overcome each barrier to inform and instigate change from all professionals and authorities, including the central government.